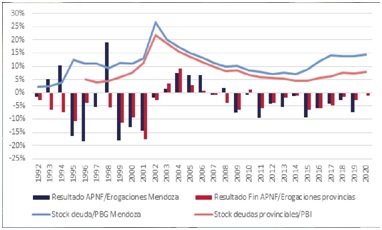

We review the evolution of provincial debt over the past thirty years, aiming to highlight key aspects necessary to understand both the causes and consequences of indebtedness.

The Origins of Provincial Debt

The issue of provincial debt, as we know it today, originates in the imposition of neoliberal policies in Argentina. During the 1976–1983 civil-military dictatorship, and later under the Menem administration, responsibilities for public health and non-university education were transferred to provincial governments without providing the corresponding financial resources to sustain them. As a result—regardless of the quality of provincial governance—Argentine provinces were pushed into growing fiscal deficits, which had to be addressed through budget cuts, public debt, or both. This is what we at the Center for Research in Critical Economics refer to as the provinces’ “structural deficit.”

This issue is further exacerbated by the deep territorial inequalities it generates in the country. These disparities stem not only from preexisting differences in provincial production structures prior to the transfer of responsibilities but also from the current system of public fund distribution. Since the early 20th century, tax revenue collection has become increasingly centralized at the national level. The federal tax revenue-sharing system, which represents a significant portion of the provinces’ funding, lacks any criteria based on population or socioeconomic conditions to determine how resources are allocated. Consequently, some provinces benefit relatively more while others are disadvantaged, regardless of their actual needs—deepening regional asymmetries.

It is also important to emphasize that the activities transferred to the provinces without sufficient funding are closely linked to the sustainability of life—areas that are predominantly supported by women, both in the domestic sphere (as evidenced by Time Use Surveys, or simply by everyday experience) and in the labor market (where women are the majority in health and education sectors). As such, these policies have a markedly regressive gender impact, in two key ways.

On one hand, when a province lacks the resources to guarantee these rights and cuts funding in these sectors, it directly affects the women working in them, as wages become the main adjustment variable in these labor-intensive activities. On the other hand, when the State withdraws from service provision or the quality of services deteriorates due to budget cuts, the burden shifts to the private sphere—where it is again women who predominantly absorb the increased caregiving responsibilities. For this reason, so-called “austerity policies” disproportionately impact women and feminized identities.

To read the full article, please visit the following link: